- By Ifat Perveen 09-Oct-2025

- 418

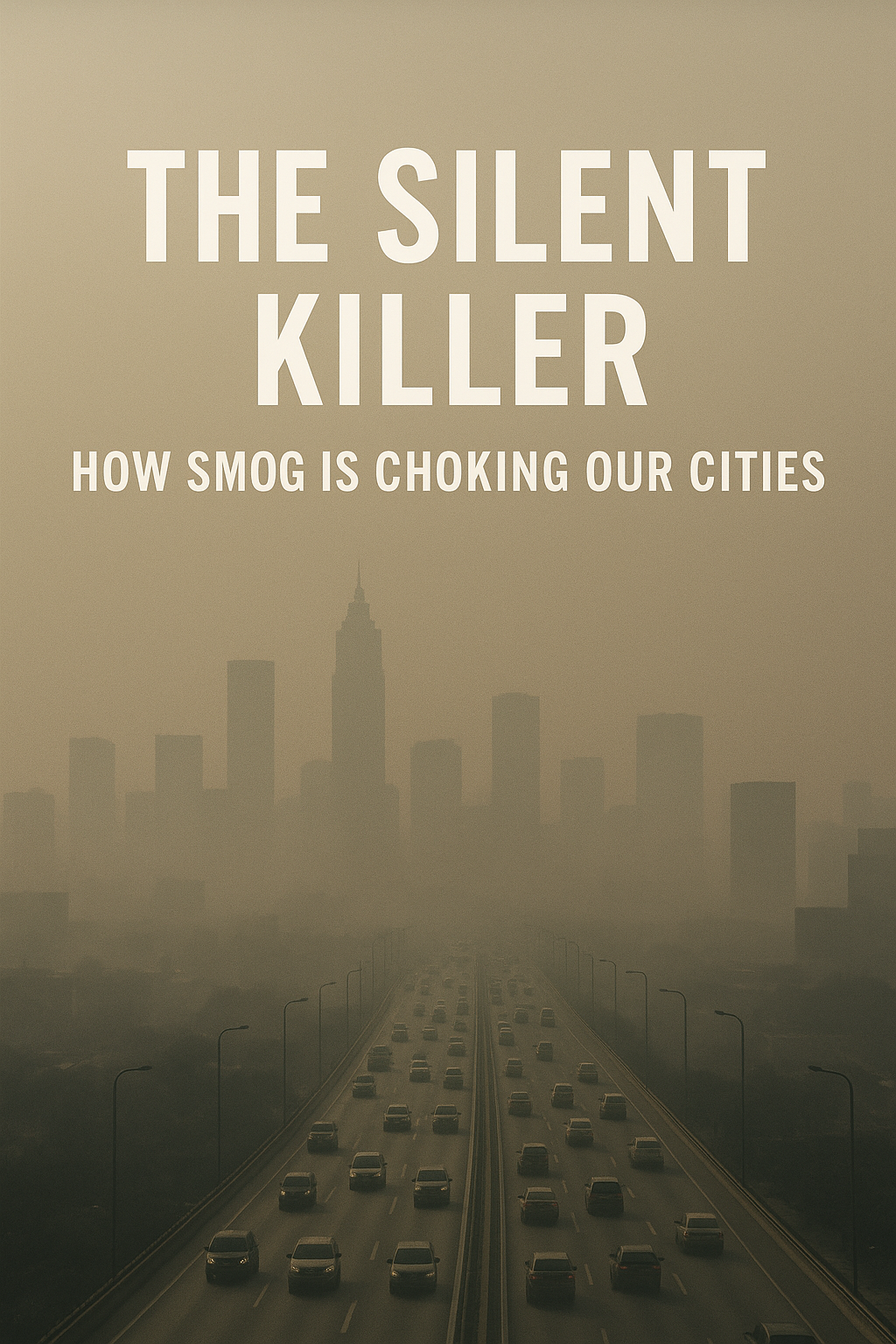

Smog, the silent killer, is suffocating our cities-polluting the air, harming health, and threatening the environment with every breath we take in harm.

Introduction:

Smog, a thick, toxic haze that hangs over highways, neighborhoods, and skylines, has become one of the defining environmental problems of modern urban life. Invisible in its early effects and dramatic when it flares into crises, smog is more than an annoyance that shortens lives, stunts development, and exacts a heavy social and economic toll. This article explains what smog is, why it forms, how it harms people and cities, and what we can do individually and collectively to improve air quality.

What is smog, really?

“Smog” is a portmanteau of “smoke” and “fog”, but the modern problem is chemically more complex. There are two main types:

-

Sulfurous song (classical smog)_ formed historically in industrial cities when sulfur dioxide (SO2) from coal combustion reacted with fog and other particulates. These types caused catastrophic events in the early 20th century.

-

Photochemical smog is a dominant urban problem today. It forms when nitrogen oxides (NOx) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are emitted by vehicles, industry, power plants, and even some consumer products react under sunlight to form ozone (O3) at ground level, plus secondary particles.

The most harmful components are fine particulate matter, particles smaller than 2.5 micrometers, and ground-level ozone. The penetrates deep into the lungs and into the bloodstream; ozone irritates the airways and reduces lung function. Both are linked to premature death from heart and lung disease.

Why has smog worsened in many cities?

Several interacting forces have made some a persistent or growing problem:

-

Urbanization and vehicle growth. More people live in cities than ever before, and rapidly rising numbers of cars, often older and poorly maintained, dramatically increase NOₓ, VOCs, and particulate emissions.

-

Industrial activity and energy sources. Coal-fired power plants, factories, brick kilns, and other industrial sources remain major PM and SO₂ emitters in many regions.

-

Geography and weather. Cities in basins, valleys, or with frequent temperature inversions (where a warm air layer traps cooler, polluted air near the ground) are natural smog magnets.

-

Climate change. Warming temperatures lengthen the season when ground-level ozone forms and worsen drought and wildfires, which add huge volumes of smoke and PM to the atmosphere.

-

Policy gaps and enforcement shortfalls. Weak regulations, lack of enforcement, or policies focused on economic growth at the expense of environmental protection let pollution accumulate.

-

Transboundary pollution. Pollution doesn’t respect borders; emissions from one region can cause smog in downwind cities, complicating accountability and mitigation.

Health Impacts: silent, systemic, and severe

Smog’s health effects are broad and striking in scale.

-

Acute effects: On high-smog days, many people experience coughing, throat irritation, and shortness of breath, eye irritation, and asthma attacks. Hospital and emergency rooms often see spikes in respiratory admissions.

-

Chronic effects: Long-term exposure to PM and ozone is linked to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), ischemic heart disease, stroke, lung cancer, and diabetes complications. Research shows that sustained pollution reduces life expectancy; even small declines in average air quality translate into many avoidable deaths.

-

Vulnerable populations: Children, the elderly, pregnant people, people with preexisting heart or lung conditions, outdoor workers, and socioeconomically disadvantaged communities bear the greatest burden. In many cities, poorer neighbourhoods are closer to highways and industrial districts, exposing residents to higher pollutant concentrations.

-

developmental harms: Prenatal and early-childhood exposure to air pollution is associated with lower birth weight, developmental delays, and worse long-term health outcomes, including reduced cognitive performance and increased risk of chronic illnesses later in life.

The result is not only suffering and lost lives but also enormous healthcare costs and lost productivity — a reminder that smog is both a public-health and an economic emergency.

Economic and social costs

Smog erodes the quality of life and economic potential:

-

Healthcare and productivity losses. Increased hospital admissions, medication needs, and missed workdays drive up costs. Chronic disease burdens persist over lifetimes.

-

Education impacts. Poor air quality forces school closures, reduces outdoor learning opportunities, and can impair children's cognitive development and school performance.

-

Investment and tourism. Persistent haze discourages tourism, reduces property values in heavily polluted areas, and can deter foreign investment.

-

Inequity. Because low-income groups often live and work in more polluted areas, smog deepens social and economic inequities, amplifying cycles of disadvantage.

Cities as illustrative case studies

While cities vary, common patterns appear worldwide.

-

Rapidly growing megacities in parts of South and Southeast Asia or Africa struggle with vehicle emissions, industrial smoke, dust from unpaved roads, and seasonal crop-burning, producing severe episodic smog.

-

Industrial legacy cities that relied on coal and heavy industry have shown that aggressive policy plus technology can reduce smog — but complacency or economic pressure can reverse gains.

-

Western cities that invested in cleaner fuels, emissions controls, public transit, and strict vehicle standards have markedly reduced many traditional pollutants; yet ozone and wildfire smoke remain rising threats under climate change.

These case studies underscore an important message: smog is solvable where political will, technology, and public demand align — but solutions must evolve as the sources of pollution change.

The role of science, technology, and data

Advances in sensors, remote sensing, data analytics, and health research are changing the fight against smog. Low-cost sensors enable community monitoring; satellite data reveal transboundary flows and wildfire smoke. Health studies increasingly quantify the benefits of incremental air-quality improvements, clarifying the economic case for action. Cities that harness this data can target interventions, evaluate progress, and make the case for funds and regulation.

A hopeful, urgent conclusion

Smog is a silent killer because it works slowly and wears down societies from the inside. Yet it is not inevitable. History shows that well-designed policy, clean technologies, and motivated citizens can drastically improve urban air. The obstacles are political and economic choices — not scientific impossibilities.

For cities to be healthy, prosperous, and equitable, clearing the air must be a top priority. That means recognizing air quality as a public good, aligning economic incentives with clean choices, and ensuring that the benefits of cleaner air reach everyone, especially those who have shouldered the worst burdens.

Every smog-free day is a win: fewer emergency-room visits, clearer skies for children to play under, greater productivity, and—most importantly—lives saved. Tackling smog is a test of whether our cities value health and future generations enough to act decisively today. The solution requires systems thinking and shared action: governments that regulate, businesses that innovate responsibly, and citizens who demand and help shape a clean future.

.png)